World

Taliban Limits Education Options, Forcing Girls into Madrasas

The return of the Taliban to power in Afghanistan in August 2021 has led to a significant shift in educational opportunities for women and girls. Many, like Nahid, a 24-year-old who was pursuing an economics degree, now find themselves attending religious schools as their only option. In a basement of a mosque in Herat, Nahid spends her mornings reciting scripture alongside 50 other women and girls, all dressed in black. She describes attending these classes as a way to combat isolation and depression, particularly as she receives a monthly stipend of 1,000 Afghanis (approximately £11).

The findings from a detailed investigation by The Guardian and Zan Times across eight provinces in Afghanistan highlight the Taliban’s systematic effort to limit educational avenues for women. Since excluding girls from secondary schools and higher education over four years ago, the regime has been establishing a network of religious schools, known as madrasas, to serve as the primary educational framework. By the end of 2023, there were over 21,000 madrasas in Afghanistan, with nearly 50 new ones built or under construction between September 2024 and February 2025 across 11 provinces.

These madrasas are managed by mullahs, who receive salaries from the education ministry. To staff these schools, the ministry has issued teaching certificates to 21,300 former madrasa students, enabling them to teach at various educational levels. As families face limited choices after the exclusion of girls from mainstream education, many are compelled to enroll their daughters in these religious institutions. This pressure is further compounded by the mullahs’ financial incentives; larger class sizes lead to higher salaries.

In the southwestern Nimroz Province, local mullahs have directly influenced families’ decisions regarding education. For instance, Karima explains that she was urged to withdraw her daughters from school in exchange for food aid promised by the local mullah. “He said he would give us food aid if I sent them to his class,” she states, lamenting that no aid materialized. Another mother, Nasreen, recounts a similar experience, stating, “Send your daughters to our religious classes or you get nothing.”

This coercive environment is reshaping community norms across Afghanistan. Families that resist enrolling their daughters face social isolation and economic hardship. Conversely, those who comply often witness a transformation in their children’s attitudes, as girls become more rigid in their thinking, sometimes even condemning their own parents as “infidels.” Reports indicate that job opportunities are increasingly reserved for families whose daughters attend these religious classes.

The situation in girls’ primary schools further illustrates the impact of the Taliban’s educational policies. Class sizes have dramatically decreased; in Nimroz, one teacher noted that 57 of her pupils left for madrasas this year. Previously, each grade would have four sections with 40 students, but now, there are only three sections with 20 to 25 students each. Many girls are caught in a dual system, attending both madrasas in the morning and primary schools in the afternoon until external pressures force them to abandon secular education entirely.

The Taliban’s restrictions extend beyond student enrollment. Experienced teachers with university degrees have been barred from teaching, replaced by teenage former madrasa students lacking formal educational training. In the western province of Farah, a headteacher recalled being ordered to dismiss five qualified teachers, with one replacement lacking even basic reading skills but possessing connections to officials and a religious school certificate.

The curriculum in madrasas is limited, focusing primarily on memorizing the Qur’an and the Taliban’s interpretations of Islamic law, gender roles, and behavioral guidelines. There is no emphasis on subjects like mathematics or science, and textbooks are imported from Pakistan, printed in Pashto, resulting in significant comprehension challenges for children in Dari-speaking regions.

Activists assert that even international aid intended for educational support is being diverted to sustain madrasas. In one incident, stationery donated by Unicef to a public school was reportedly redirected to a mullah’s class, with the school janitor instructed to misrecord the supplies as “misplaced.”

The ongoing expansion of madrasas is also altering the job market in Afghanistan. Civil servants with years of experience are being replaced by young madrasa graduates. In Nimroz, an activist shared the story of a woman with a bachelor’s degree and two decades of experience in the women’s affairs department who was dismissed without explanation, her position taken by a 17-year-old madrasa graduate. The message is clear: “If you want a job, forget university. Go to the madrasa.”

As a result, the aspirations of young women are changing. Girls interviewed in the region report that their dreams of becoming doctors or engineers have been replaced by the understanding that madrasa certificates are increasingly viewed as the only viable qualifications. For Nahid, the experience of attending a madrasa is particularly poignant. While it provides her a temporary escape from solitude and despair, it confines her within an ideological framework she does not accept. “If I stay home, I will lose my mind,” she reflects. “If I go, at least I see other women.”

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoNeurologist Warns Excessive Use of Supplements Can Harm Brain

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoFiona Phillips’ Husband Shares Heartfelt Update on Her Alzheimer’s Journey

-

Science1 month ago

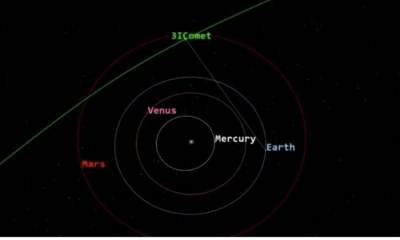

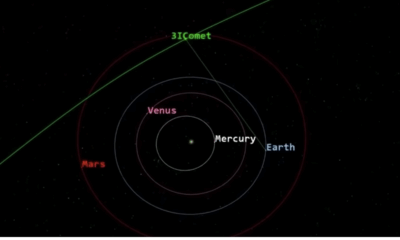

Science1 month agoBrian Cox Addresses Claims of Alien Probe in 3I/ATLAS Discovery

-

Science1 month ago

Science1 month agoNASA Investigates Unusual Comet 3I/ATLAS; New Findings Emerge

-

Science4 weeks ago

Science4 weeks agoScientists Examine 3I/ATLAS: Alien Artifact or Cosmic Oddity?

-

Entertainment4 months ago

Entertainment4 months agoKerry Katona Discusses Future Baby Plans and Brian McFadden’s Wedding

-

Science4 weeks ago

Science4 weeks agoNASA Investigates Speedy Object 3I/ATLAS, Sparking Speculation

-

Entertainment4 months ago

Entertainment4 months agoEmmerdale Faces Tension as Dylan and April’s Lives Hang in the Balance

-

World3 months ago

World3 months agoCole Palmer’s Cryptic Message to Kobbie Mainoo Following Loan Talks

-

Science4 weeks ago

Science4 weeks agoNASA Scientists Explore Origins of 3I/ATLAS, a Fast-Moving Visitor

-

Entertainment4 months ago

Entertainment4 months agoLove Island Star Toni Laite’s Mother Expresses Disappointment Over Coupling Decision

-

Entertainment3 months ago

Entertainment3 months agoMajor Cast Changes at Coronation Street: Exits and Returns in 2025