Science

Physicists Reveal Internal Structure of Radium Monofluoride

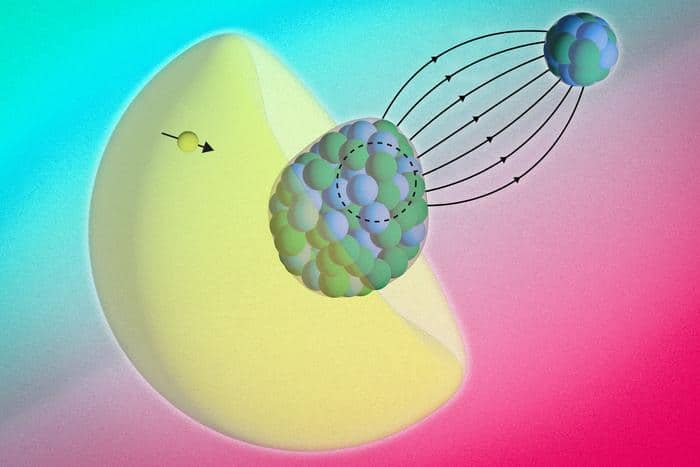

Physicists have successfully captured the first detailed image of the internal structure of radium monofluoride (RaF), utilizing the molecule’s own electrons to probe its nucleus. This breakthrough, led by researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), marks the initial observation of the Bohr-Weisskopf effect within a molecule. Co-leader of the study, Shane Wilkins, emphasizes that this achievement is a significant step toward investigating nuclear symmetry violation, a phenomenon that could elucidate why our universe comprises far more matter than antimatter.

Radium monofluoride contains the radioactive isotope 225 Ra, which is challenging to produce and measure. The isotope is generated in minute quantities at specialized accelerator facilities, requiring high temperatures and velocities for creation. With a nuclear half-life of approximately 15 days, only small amounts—less than a nanogram—are available for research, presenting considerable difficulties compared to stable molecules.

Wilkins, who conducted the measurements within Ronald Fernando Garcia Ruiz‘s research group at MIT, highlights the complexities involved. “We need extremely selective and sensitive techniques to elucidate the structure of molecules containing 225 Ra,” he notes. The research team opted for RaF due to its predicted sensitivity to subtle nuclear effects that disrupt natural symmetries. As Silviu-Marian Udrescu, the study’s other co-leader, elaborates, the radium atom’s nucleus exhibits an octupole deformation, giving it a pear-like shape—unlike most atomic nuclei.

Understanding RaF’s Internal Dynamics

The study, published in the journal Science, involved collaboration with scientists from CERN, the University of Manchester in the UK, and KU Leuven in the Netherlands. The focus was on RaF’s hyperfine structure, which emerges from the interactions between nuclear and electron spins. These interactions can yield valuable insights regarding the distribution of protons and neutrons within the nucleus.

Traditionally, physicists consider electron-nucleus interactions to occur over relatively long distances. In the case of RaF, the situation differs significantly. Udrescu describes the electrons of the radium atom as being “squeezed” within the molecule, enhancing their likelihood of penetrating the radium nucleus. This unique behavior results in a slight shift in the energy levels of the electrons, which the research team confirmed through precise measurements and advanced molecular structure calculations.

“We observe a clear breakdown of the long-range interactions model because the electrons spend a significant amount of time within the nucleus itself due to the special properties of this radium molecule,” Wilkins explains. “The electrons thus act as highly sensitive probes to study phenomena inside the nucleus.”

Implications for Future Research

The findings from this research lay the groundwork for future experiments aimed at exploring nuclear symmetry violation and testing theories that extend beyond the Standard Model of particle physics. The Standard Model posits that every matter particle, from baryons like protons to leptons such as electrons, should have a corresponding antiparticle identical in every respect except for charge and magnetic properties.

Despite these predictions, the Standard Model suggests that the Big Bang, which occurred nearly 14 billion years ago, should have produced equal amounts of matter and antimatter. Current observations reveal a universe predominantly composed of matter. Subtle differences between matter particles and their antimatter counterparts may account for this disparity, leading physicists to seek these distinctions to explain the matter-antimatter asymmetry.

Wilkins asserts that the team’s research will be vital for future explorations of radioactive species like RaF. Currently, he is developing a new setup at Michigan State University’s Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB) to cool and slow beams of radioactive molecules. This advance will facilitate higher-precision spectroscopy related to nuclear structure, fundamental symmetries, and astrophysics.

The long-term objective of Wilkins and his collaborators in the RaX collaboration, which includes teams from FRIB, MIT, Harvard University, and the California Institute of Technology, is to implement advanced laser-based techniques employing radium-containing molecules. This ambitious project aims to deepen our understanding of the universe’s fundamental components and their behaviors.

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoNeurologist Warns Excessive Use of Supplements Can Harm Brain

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoFiona Phillips’ Husband Shares Heartfelt Update on Her Alzheimer’s Journey

-

Science2 months ago

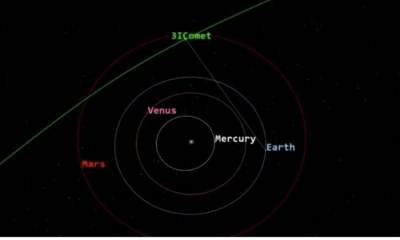

Science2 months agoBrian Cox Addresses Claims of Alien Probe in 3I/ATLAS Discovery

-

Science2 months ago

Science2 months agoNASA Investigates Unusual Comet 3I/ATLAS; New Findings Emerge

-

Science1 month ago

Science1 month agoScientists Examine 3I/ATLAS: Alien Artifact or Cosmic Oddity?

-

Entertainment5 months ago

Entertainment5 months agoKerry Katona Discusses Future Baby Plans and Brian McFadden’s Wedding

-

Science1 month ago

Science1 month agoNASA Investigates Speedy Object 3I/ATLAS, Sparking Speculation

-

Entertainment4 months ago

Entertainment4 months agoEmmerdale Faces Tension as Dylan and April’s Lives Hang in the Balance

-

World3 months ago

World3 months agoCole Palmer’s Cryptic Message to Kobbie Mainoo Following Loan Talks

-

Science1 month ago

Science1 month agoNASA Scientists Explore Origins of 3I/ATLAS, a Fast-Moving Visitor

-

Entertainment2 months ago

Entertainment2 months agoLewis Cope Addresses Accusations of Dance Training Advantage

-

Entertainment3 months ago

Entertainment3 months agoMajor Cast Changes at Coronation Street: Exits and Returns in 2025