Sports

Art as Transformation: Timo Skrandies Explores Joseph Beuys’ Legacy

In a world grappling with climate crisis, societal divides, and digital saturation, the ideas of Joseph Beuys about “social sculpture” continue to resonate. German theorist and aesthetician Professor Timo Skrandies from Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf will address Beuys’ enduring impact during his lecture titled “Expanded Concept of Art (Joseph Beuys): Artistic Practice and Social Sculpture.” The lecture takes place today at 12:00 at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Cetinje, followed by another session at 18:30 at the European House in Bar.

Skrandies, a leading researcher of Beuys’ life and work, will discuss art as a space for transformation, empathy, and collective action. He emphasizes that these themes are crucial for understanding our existence in today’s “critical zone.” This lecture is part of a program organized by the Faculty of Fine Arts to coincide with the exhibition “I Want to See My Mountains,” inspired by Beuys’ ambient installation. The exhibition is realized in cooperation with the Federal Republic of Germany’s Embassy in Podgorica and the Institute for Foreign Relations.

In an interview with Pobjeda, Skrandies reflects on Beuys’ legacy in the contemporary world, particularly the role of art in addressing pressing issues. He notes, “Beuys’ art was not only provocative; it was also a sincere attempt to redefine creativity and democracy.” He underscores that every individual possesses the creative potential to impact society, a view central to Beuys’ philosophy.

Skrandies acknowledges that although Beuys passed away in 1986, well before the reunification of Germany and the end of the global East-West divide, his relevance persists. He cites two primary reasons for this: Beuys’ influence on subsequent artists—such as Marina Abramović and Anselm Kiefer—and his engagement with issues that continue to affect us today, including ecological crises, equality, and the future of Europe.

The conversation shifts to Beuys’ famous assertion that “everyone is an artist.” Skrandies interprets this statement as both a provocation and an honest reflection of the human condition. He explains that this idea encourages individuals to see their actions as inherently creative, fostering social connections and enabling collective societal transformation.

Skrandies’ research delves into “art in the Anthropocene” and “aesthetics of the critical zone.” He connects Beuys’ work to contemporary ecological and philosophical discussions, emphasizing that Beuys was one of the first artists to address ecological issues. His activities, particularly in Italy, highlighted the importance of environmental protection during a time when such topics were barely acknowledged.

Critics often argue that Beuys blurred the lines between art and life, myth and history. Skrandies acknowledges this complexity, suggesting that Beuys’ approach challenges conventional distinctions and invites a re-examination of how art interacts with various aspects of existence. He refers to the work of French philosopher and sociologist Bruno Latour to support the idea that our understanding of modernity may be misguided, as different forms of existence—be they natural, cultural, or technical—are interwoven and influence each other.

Skrandies also discusses Beuys’ use of materials such as felt, fat, and honey, which carry symbolic and tactile significance. He describes transformation as a key concept in Beuys’ oeuvre, where materials reflect energetic processes and societal meanings. For instance, Beuys’ felt suit may serve as a source of warmth and healing, while the delicate lines in his animal drawings reveal vulnerability.

The dialogue extends to the notion of “political art” and the potential of Beuys’ social sculpture to offer a meaningful framework for engaging with political and ethical commitments through art in the 21st century. Skrandies posits that social sculpture encapsulates how our thoughts, feelings, and actions are in constant flux and interconnected. He stresses that the responsibility for societal conditions cannot be shifted to others; we all contribute to the collective experience.

In closing, Skrandies expresses hope that the audience in Montenegro will grasp the importance of dialogue in navigating our lives within this critical zone. He warns against the “greatest misunderstanding” that could arise from concluding that Beuys’ work is complete. Instead, he advocates for ongoing discussions about Beuys’ art and its implications for society today.

As Skrandies prepares to share his insights, he aims to inspire a deeper understanding of the relationship between art, ecology, and collective imagination, reminding us all of our role in shaping the world around us.

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoNeurologist Warns Excessive Use of Supplements Can Harm Brain

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoFiona Phillips’ Husband Shares Heartfelt Update on Her Alzheimer’s Journey

-

Science2 months ago

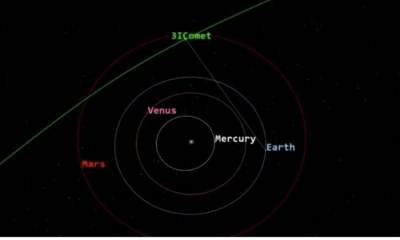

Science2 months agoBrian Cox Addresses Claims of Alien Probe in 3I/ATLAS Discovery

-

Science2 months ago

Science2 months agoNASA Investigates Unusual Comet 3I/ATLAS; New Findings Emerge

-

Science2 months ago

Science2 months agoScientists Examine 3I/ATLAS: Alien Artifact or Cosmic Oddity?

-

Entertainment2 months ago

Entertainment2 months agoLewis Cope Addresses Accusations of Dance Training Advantage

-

Entertainment5 months ago

Entertainment5 months agoKerry Katona Discusses Future Baby Plans and Brian McFadden’s Wedding

-

Science2 months ago

Science2 months agoNASA Investigates Speedy Object 3I/ATLAS, Sparking Speculation

-

Entertainment5 months ago

Entertainment5 months agoEmmerdale Faces Tension as Dylan and April’s Lives Hang in the Balance

-

Entertainment2 days ago

Entertainment2 days agoAndrew Pierce Confirms Departure from ITV’s Good Morning Britain

-

World3 months ago

World3 months agoCole Palmer’s Cryptic Message to Kobbie Mainoo Following Loan Talks

-

World4 weeks ago

World4 weeks agoBailey and Rebecca Announce Heartbreaking Split After MAFS Reunion